the eight mountains

Felix van Groeningen’s and Charlotte Vandermeersch’s The Eight Mountains tells a decades-spanning tale that manages to be both epic in scope and yet intimate in its scale. Based on the novel by Paolo Cognetti, the title comes from a fable related to one of the characters by a fellow travler. The world is made of eight mountains and eight seas, with another, even taller mountain in the middle, Mount Umeru. The traveler asks, who then will have learnt more, the person who’s traveled the eight mountains and seas, or the person who’s climbed the single tallest mountain in the middle? The directing duo cleverly explore this dilemma in their movie, chronicling the lifelong friendship between two men with vastly different life experiences yet brought together by the same mountain.

The story begins in 1984, with young Pietro (Lupo Barbiero) and his mother Francesca (Elena Lietti), who are vacationing in Grana, a remote Italian mountain village. There he meets a local boy his age, Bruno (Cristiano Sassella). The two are essentially latchkey kids, going about their lives with minimal parental supervision. Pietro’s father Giovanni (Filippo Timi) is working as an engineer back home in Turin. Bruno is tightlipped about his parental situation—he claims his father is working abroad as a bricklayer and refuses to share details about his mother. The two boys quickly establish a friendship, and with the arrival of Pietro’s father, the 3 of them frequently go for hikes on the stunningly beautiful mountains nearby. Seeing that he needs an education (he struggles with reading) and stronger supports, Pietro’s parents offer to take Bruno with them back home. Bruno’s father rejects the offer, and suddenly, years pass before the two boys see each other again, this time as teenagers.

The movie proceeds in this fashion, covering a roughly 30-year period as the two boys, and then men, see their friendship develop in fits and starts. It’s an ambitious length of time to cover in a feature film, and combined with the frequently jaw-dropping vistas, it makes the movie feel suitably grand and epic. (This really is a stunningly beautiful film, shot in Italy and Nepal, and filmed in a square aspect ratio that emphasizes the painterly feel of the movie. I kept waiting for there to be an ugly shot; it never came.) Adding to the epic feel is the unhurried nature of the plotting. Similar to movies like The Godfather, the directors aren’t concerned with covering a specific plot per se. Rather, their focus is on simply observing these characters as they go through different stages of their life.

The bulk of the movie takes place decades later, when both men, roughly in their 30s, reunite in Grana after Pietro’s father passes away. Though Pietro (now played by Luca Marinelli) hadn’t talked to his father ever since a falling out several years prior, his father has left him a plot of land on one of the mountains, a ruin named Barma Drola. He initially despairs, “I’ve inherited a pile of rocks.”

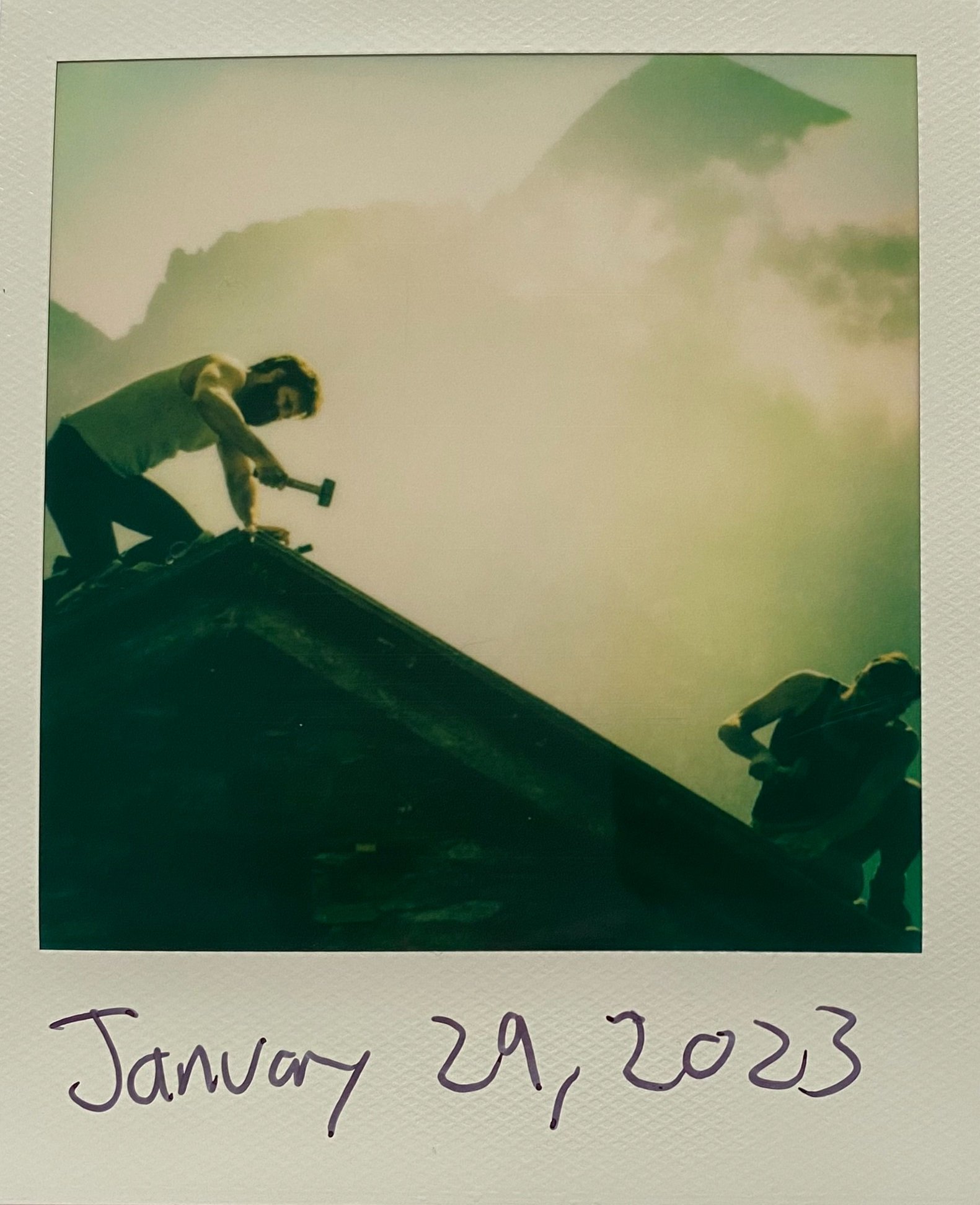

However he discovers that, for many years, Bruno (now played by Alessandro Borghi) had become close to Pietro’s father, the two of them going on hikes together and developing a father-son bond of their own. Indeed Pietro’s father had made Bruno promise to build this house, making Pietro, and the audience, question who the house is really meant for. This is where the movie begins to acquire some dramatic tension, though in a low register. The two men are rather taciturn and not overly psychologically minded. They’re not particularly keen on introspection, and their bond largely strengthens not through dramatic conversations but small gestures as well as the passage of time. In a lovely sequence, the two begin the painstaking task of building the house brick by brick, and there’s a lovely, tactile feel to this throughout. We watch as they slowly remove rotted roof beams, sliding new ones into place. It’s hard work, and as the house slowly comes together, the two men noticeably become closer. There are also some rare moments of humor here. At one point, Pietro, exhausted, muses about going on a hike. Bruno then throws an apple at him, insisting he treat himself. Later, returning from his hike, Pietro does a charming little dance, clearly appreciative of his friend for allowing him this small respite.

Just as they’ve completed the house and decided it belongs to both of them, their paths diverge again, and this is where the eight mountains metaphor becomes more apparent. Bruno is clearly the traveler who’s climbed the central mountain, the country boy who’s lived in Grana all his life. Pietro is the more urban, worldly traveler who (at this point in the movie) embarks on travels around the world, most significantly to Nepal. They’ve both bonded over their mutual home in Grana and both have an appreciation for nature and appear to be at peace with themselves. Is one perspective more valid than the other? Is one of them more knowledgeable? It’s a fascinating question, as these two men’s lives have diverged in significant ways.

In keeping the story intimately focused on the two men, the filmmaking duo’s response seems to be, who cares? The movie is careful not to overly condemn or praise either character, both of whom have their faults. Pietro, having spent his life in the city surrounded by a glut of choices, finds himself paralyzed as an adult, unsure what he wants or what he should do. Much of the second half of the movie consists of his efforts to rectify this, and to understand himself. Conversely, Bruno seems more self-assured from the start, with a keener sense of his own needs and desires. Yet in limiting himself to Grana, and then to his almost monomaniacal vision of running his uncle’s alpeggio (a mountain pasture), he reveals his own biases. He becomes fixated on his goals that when life begins to put obstacles in his way, he finds himself unable to veer from the path, unable to adapt.

In the hands of lesser directors, this movie easily could’ve fallen victim to its own scale, as the story practically begs for a maximalist approach. However, in keeping the story grounded in the two men and their relationship, the movie feels relaxingly low key. Make no mistake, the movie does veer into some heavy thematic territory, as the two men find themselves having to overcome challenges in their own lives. Not only are they seeking self-fulfillment, but they also both, in their own ways, grapple with the question of legacy. That is, what are they leaving behind for the world, and for their loved ones? It’s a question particularly prominent in Pietro’s mind, as he retraces his father’s steps and discovers his hiking journal detailing his and Bruno’s journeys together. There’s a reassuring sense of propulsion here, as the two men find themselves drawn inexorably, inevitably forward. Despite the heartbreak they suffer, they find that they have to keep moving, or risk becoming a victim of their own stagnancy. As Pietro learns by the end of the film, there are some mountains you can’t return to, most of all the mountain that’s at the center of all the others.