fantastic machine

Fantastic Machine, the centuries-spanning documentary from Axel Danielson and Maximilien Van Aertryck, examines the history of image-making and its ever-evolving relationship to society. Compiled from an exhaustive supply of footage, reportedly sourced by the directors over a 10-year span, the project is impressive in its sheer breadth. While the scope dampens the film’s intellectual aspirations, this is still a mostly fascinating, frolicking look at what it means to make images, both ontologically and practically.

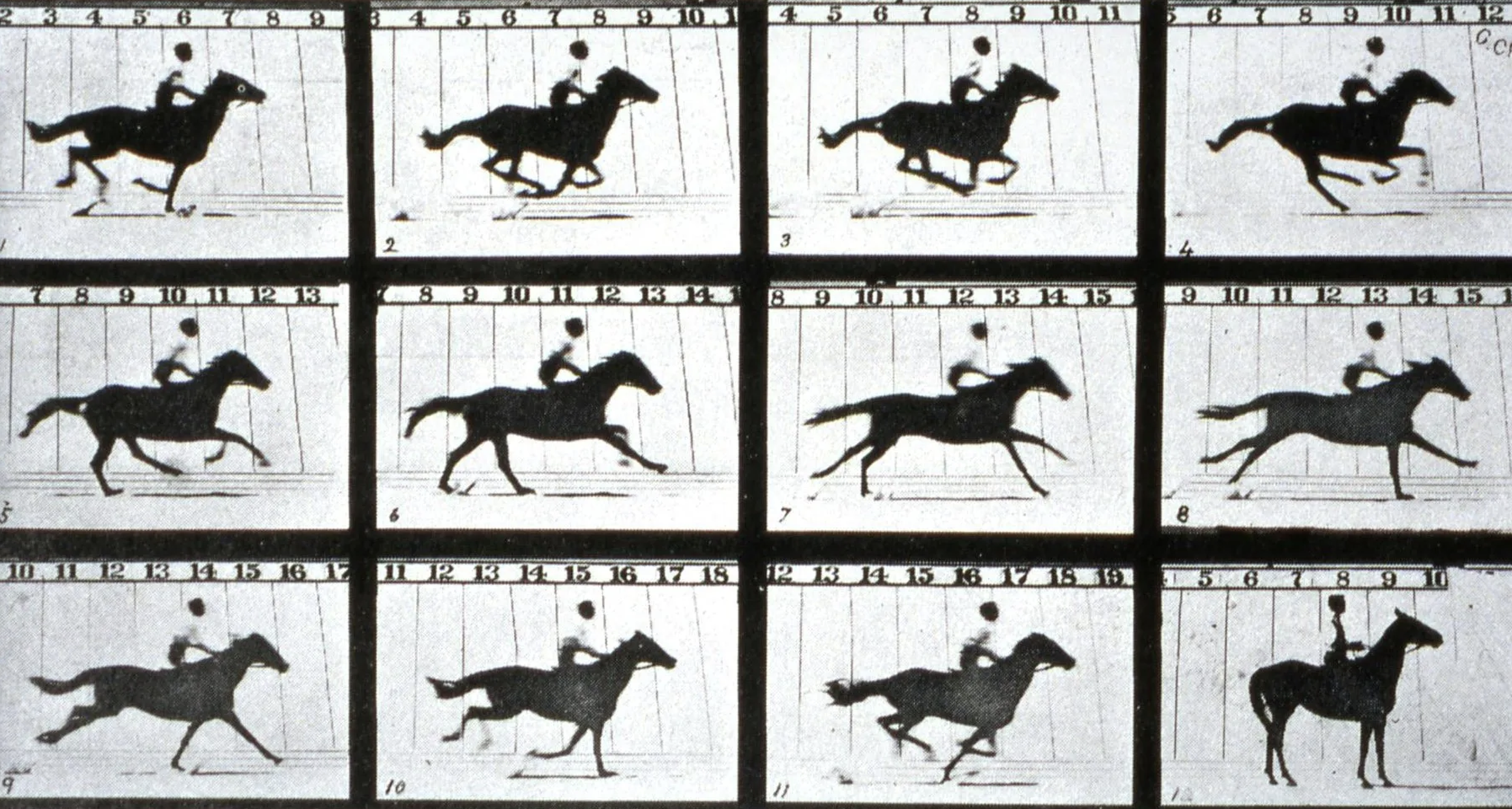

The film begins with an amusing, user-generated anecdotal video. A woman, recording on her smartphone, captures an inverted image on her bedroom wall, shocked at what she’s seeing. The street outside has been replicated on her wall, albeit upside down, and the level of detail is impressive—even down to the cars driving by. Eventually, the doc jumps back to 1828, when the French inventor, Nicephore Niepce created the world’s oldest preserved photograph, on a tin plate. From here, the filmmakers give a history lesson of shorts, tracing the evolution of photography into motion pictures, then television, and finally into social media and viral videos on the internet.

At each juncture, the filmmaking duo stop to consider the implications of the latest leap forward in technology and what it means for human society. With impressive speed, people learn to use image-making for their own means. After the debut of 1895’s “A Train Arrives at Le Ciotat,” people instantly discover that they can use it to record sporting events and to create fictional stories, both grounded and fantastical. Later in the 20th century, we watch as cinema gets used as a means of staging reality, of distorting the truth. In one fascinating interlude, Leni Riefenstahl, director and editor of Hitler’s propaganda videos, gleefully breaks down how she edited one of his rallies, boasting about how she used a telephoto lens to make the lines of banners look lush. The emotional disconnect between material and filmmaker is repugnant and fascinating.

The documentary is full of anecdotes and interviews like this, examining the ways that both individuals and larger entities seek to manipulate images for their own gains. From despots disseminating propaganda, to Allied forces faced with the daunting task of convincing the world that, yes, the Holocaust did happen, the filmmakers trace a line all the way to our present. The last third or so of the film focuses largely on viral videos, on memes that sparked cultural conversations at the time but also continue to raise larger questions. One particularly disturbing interlude shows a prominent YouTuber being swatted as he livestreams, his followers putting him in danger simply because they can.

Compared to say, All Light, Everywhere, a recent Sundance film that explored similar issues but with a much tighter focus, Fantastic Machine’s massive scope prevents it from delving too deeply into any one issue. Instead, the filmmakers are content to highlight an issue, let it linger for a few seconds, and then move on to the next hot-button topic. As such, this ends up feeling more like an Intro 101 course. It’s fun, and absolutely worth attending—necessary, rather. But when it ends, you find yourself looking forward to more incisive, profound, advanced courses. A prime example is the film’s discussion of mass shootings. The directors share an all-too-brief snippet from a 2009 interview in which a psychiatrist implores newscasters to stop broadcasting images of mass murders, because doing so propagates such killings. Before the impact of his plea can land, the film hurries off to the next vignette, off to the next amusing, “hey, I remember that” viral video.