a little prayer

As Angus Maclachlan so succinctly phrased it in the Q and A for the Sundance premiere of his film A Little Prayer, family is about not always knowing what’s going on with each other There are limits to how well we can know each other, and limits to our ability to influence others’ actions. Part of learning to exist withn a family means to acknowledge our own limits. Maclachlan’s film beautifully explores this implicit truth in his film, particularly as it’s told through the lens of Southerners, who are often stereotyped as keeping their feelings to themselves and being averse to difficult conversations. The result is an intimate, authentic, and deeply personal look at one Southern family, full of empathetic, warm performances.

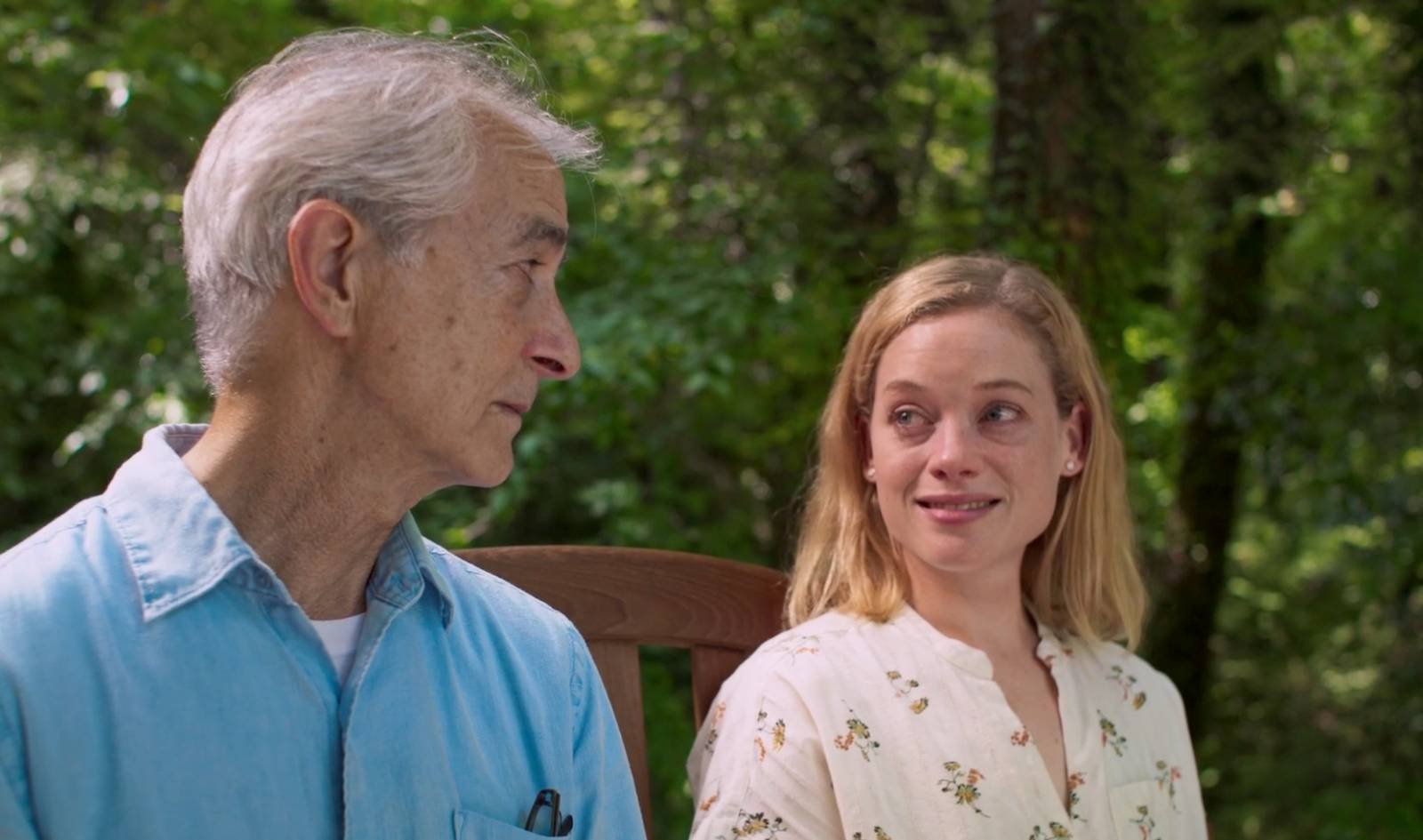

Set (and filmed) entirely in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, we first meet Tammy (Jane Levy) and David (Will Pullen), who live in a guesthouse on his parents’ property. A gospel singer can be heard on the soundtrack, crooning, “who’ll rock the cradle when I’m gone,” hinting at the film’s themes of legacy and generational transitions. David is fully clothed, lying on top of the bedsheets, while Tammy stares up at the ceiling, lost in thought. Her quant, comforting morning ritual then consists of spending time with the in-laws, Bill (David Strathairn) and Verida (Celia Weston), and making bag lunches for David and Bill, who work together at their long-time family business. At the office, Bill notices a flirtation between David and the office secretary, Narcedalia (Dascha Polanco) and begins to worry that his son may be having an affair. Between this disquieting realization and the unexpected arrival of his daughter Patti (a hilariously trashy Anna Camp) and granddaughter Hadley (Billie Roy), Bill is forced to confront the limits of his own influence and ability to help the ones he loves.

From the start, this is an exquisitely lived-in film, with the naturalistic performances and the easy-going chemistry among the family members—everyone but David, that is. Tammy and Bill have a relaxed chemistry, trading sly jokes and displaying genuine concern for one another. A favorite pastime of theirs is debating the merits of the gospel singer who wakes up the neighborhood every morning with her loud singing. When the plot later takes a turn into darker territory, the singing conspicuously stops, suggesting a mutual sense of loss for Tammy and Bill. Similarly, Verida and Bill seem to have their own unspoken language, having entire conversations with minimal dialogue, relying on pregnant glances and their decades-spanning intimacy to know what the other is thinking.

The film uses a 1.59 aspect ratio, which makes the viewer feel as if they’re peering through a canvas. This feeling is accentuated by the soft, naturalistic cinematography, which often accentuates the warm colors of the characters’ environment. Winston-Salem truly feels like a character of its own, and any time the characters go for a walk, it’s always stunning to see the sunlight dappling down through the trees overhead. At one point, two of the characters visit an art museum, complimenting the paintings on their exquisite details and evocation of the sublime. It feels very meta, as if they’re discussing the film itself.

The emotions on display in the film, with a few exceptions, are largely restrained and understated. There’s a low-key humor to the banter between Tammy and Bill, and essentially any of Weston’s line readings, with her delightful Southern drawl (they all have Southern accents, but hers is particularly enjoyable). Maclachlan also wrings some nervous laughter out of Patti’s trashiness. Camp sinks her teeth into the role, and while her approach is a bit broader than her castmates’, it works for the character, and only highlights how strong the bonds are between the rest of the family (again, except for David). Patti is a force of nature, wearing flip flops, dropping f-bombs, and looking for treasure in the backyard with her metal detector. In other words, she’s the perfect stereotype of a low-class Southerner (think Hilary Swank’s character’s family in Million Dollar Baby).

Though this is an ensemble cast, the movie arguably belongs to Levy and especially Strathairn. From the opening scenes, Stathairn’s patriarch is so well-intentioned and caring that I’d petition for him to replace Tom Hanks as America’s Dad. Much of the film consists of him attempting to resolve his family’s interpersonal crises, and Strathairn perfectly telegraphs the tension between wanting to help his children and minding his own business (in other words, being a good Southerner). In one particularly touching late-film exchange, Bill sinks into a chair, quietly admitting that perhaps his actions haven’t really helped anyone at all. Indeed, he and Verida have a heart to heart, where she tells him that, as parents, they can only do so much. Much of the film’s dramatic stakes revolve around Bill’s attempts to help his family, to mixed results. In a smaller but still central role, Levy is key as the daughter-in-law who is also torn between two impulses—to be a part of the family that has been so good to her, and to be honest with herself. Some of the movie’s rare bursts of emotion are due to her character,

Maclachlan’s touch is so light that at times it’s easy to forget all the difficult topics the movie tackles, from infidelity to abortion to veterans’ mental health and PTSD. His approach is never showy nor didactic. There are no big, impassioned speeches here—only quietly uttered lines and looks of realization. And all these topics are grounded, again, in these fine, lived-in performances. These truly seem like living, breathing people, and every character has their own agency. Maclachlan doesn’t condescend to designate any of the characters as being undeserving of respect. Even David, arguably the closest thing to a villain in this story is portrayed with empathy, as a broken man unable to escape his traumas and patterns of behavior.

This is easily one of the most enjoyable films to come out of Sundance this year, with its refreshingly realistic take on a Southern family who all, for the most part, are just trying to do right by each other. Despite the regional specificity, the themes covered in this film are universal, and transcend cultural delineations. Maclachlan’s movie works beautifully both as a tribute to his hometown and an acknowledgement of the struggles that families often go through but perhaps are unable, or unwilling, to put a name to. In addressing taboo topics through the lens of this deeply human, relatable Southern family, the film offers up a tacit acknowledgement of the limits of familial influence. We can’t always help the ones we love, and sometimes learning to be okay with that can bring us closer together.